Sign up for CNN’s Wonder Theory science newsletter. Explore the universe with news of fascinating discoveries, scientific advances and more.

CNN

—

This year, scientists were able to uncover the mysteries surrounding figures throughout history, both known and unknown, to reveal more of their unique stories.

In some cases, analysis of ancient DNA has helped fill knowledge gaps and change preconceived notions. A prime example is how DNA research is reshaping the way people understand the archaeological site of Pompeii, which remained trapped under a layer of ash thousands of years after the eruption of Mount Vesuvius in AD 79 wiped out the Roman city.

Genetic traces collected from the victims’ bones showed that what was once considered a mother holding her son in her final moments was an unrelated adult male who likely provided comfort to the child before he died, and they challenged other long-standing assumptions.

Here are some methods of knowledge It has sparked new understandings of historical figures in 2024 and, in some cases, led to more mysteries that remain unsolved.

Detailed analysis of tooth enamel, tartar and bone collagen has helped researchers uncover details about “Vitrup Man”, a Stone Age migrant who died violently in a bog in northwestern Denmark about 5,200 years ago.

His remains, recovered from a peat bog in Vitrup, Denmark, in 1915, were found next to a wooden club that was likely used to hit him on the head. But little was known about him.

Using sophisticated analytical methods, Anders Fischer, a project researcher at the Department of Historical Studies at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden, and his colleagues set out to “find the individual behind the greatness” and tell the story of the world’s oldest known immigrant. History of Denmark.

Vitrup Man grew up along the Scandinavian coast and belonged to a hunter-gatherer community, enjoying a diet of fish, seals, and whales. But his life changed radically in his late teens when he moved to Denmark and switched to a farmers’ diet, eating sheep and goats. He died between 30 and 40 years old.

Vittrup Man may have been killed as a sacrifice, or perhaps he was in the wrong place at the wrong time. But Fisher found it fun to use multiple techniques to reveal aspects of his identity.

“In the case of Vitrup, we meet a real first-generation immigrant and can follow his remarkable geographical and nutritional shift from northern to southern Scandinavia and from fisherman to farmer lifestyle,” he said.

Separately, researchers were able to link the identity of the skeleton found in the castle well to a passage from an 800-year-old Scandinavian text.

The Sverres Saga, which tells the story of the true king Sverre Sigurdsson, includes a description of an invading army dumping the body of a dead man into a well at Sverresborg Castle in Norway in 1197 in a possible attempt to poison the water supply.

A team of scientists recently studied the bones discovered in the citadel’s well in 1938. Using radiocarbon dating, the researchers determined that the remains were about 900 years old. Genetic sequencing of tooth samples showed that the “good guy” had medium skin tone, blue eyes, and light brown or blond hair. In a twist, its genes cannot be traced back to the local population.

“The biggest surprise for all of us was that the Virtuous Man did not come from the local population, but rather that his ancestors go back to a specific region in southern Norway,” said study co-author Michael D. Martin, a professor in the Department of Natural History at the Norwegian University of Science and Technology Museum in Trondheim. , in October: “This indicates that the siege army threw one of its dead into the well.”

Improvements in molecular genetics over nearly two decades have helped researchers solve a long-standing historical mystery of the so-called “Lost Prince” who seemingly appeared out of nowhere in mid-19th century Germany.

For 200 years, there has been speculation that a mysterious man named Kaspar Hauser was a secret member of the German royal family. When he was found wandering without an identity in Nuremberg in May 1828 at the age of 16, Hauser was barely able to communicate with his interrogators.

A story about Hauser being a kidnapped prince, taken from the royal family of Baden in what is now southwestern Germany, spread like wildfire.

There have been multiple studies of genetic data from Hauser subjects, but conflicting results have led to dead ends with no answers.

This year, researchers conducted a new analysis of Hauser’s hair samples and were able to prove that the mitochondrial DNA, or genetic code passed down from the mother’s side, did not match the mitochondrial DNA of the Baden family.

The refutation of the royal hoax may have solved one mystery, but another has taken its place. Just who was this man? As his tombstone reads, Hauser remains “the mystery of his time.”

Classical composer Ludwig van Beethoven died at the age of 56 in 1827 after a long struggle with illnesses including deafness, liver disease, and gastrointestinal illness. The composer expressed his desire to study his illnesses and share them “at least as much as possible so that the world will be reconciled with me after my death.”

In May, researchers published a study showing high levels of lead were detected in documented locks of Beethoven’s hair, and suggested that the composer was suffering from lead poisoning, which may have contributed to his recurring health problems.

The findings built on what was previously discovered after Beethoven’s genome was made available to the public to investigate the complex nuances of its health.

In addition to lead, Beethoven’s locks also contained increasing amounts of arsenic and mercury, but how did they get there? These substances likely resulted from the accumulation of a lifelong diet of fish from the polluted Danube River and wine, which had been sweetened and preserved with lead.

The new results add to a better understanding of the composer as well as the complex and sweeping symphonies he left behind and which are still played by orchestras around the world.

“People say, ‘Music is music, so why do we need to know any of this stuff?’” “But in Beethoven’s life, there is a connection between his suffering and the music,” William Meredith, a Beethoven researcher and co-author of the study, said in May.

Colonial secrets and scandals

The study of skeletal remains using new DNA analysis techniques shed light on the fate of family members of the first US president, George Washington, last March.

Washington’s younger brother Samuel, who died in 1781, was buried with 19 other family members in a cemetery on Samuel’s estate near Charles Town, West Virginia.

But some graves were unmarked, likely to prevent grave robbing. Courtney L said: Cavagnino, a research scientist at the Armed Forces DNA Identification Laboratory of the Armed Forces Medical Examiner System, told CNN in March.

Cavagnino led a team that studied the remains exhumed from the tomb in 1999, and identified two of Samuel’s grandchildren as well as their mother. The study team conducted excavations to find Samuel’s final resting place, but the location of his grave remains a mystery.

However, the techniques used in the study could be used to identify the unidentified remains of those who served in the military, dating back to World War II.

Meanwhile, a separate investigation is underway Unmarked graves found at the British settlement of Jamestown, Virginia, have revealed a long-hidden scandal within the family of the colony’s first governor, Thomas West.

The researchers analyzed DNA from two male skeletons inside the graves, and both men were related to the West through a common maternal lineage. One of the men, Captain William West, was born to West’s spinster aunt, Elizabeth—and illegitimate.

The researchers found that West’s birth details had been deliberately removed from family genealogy records at the time, suggesting that the secret of his true lineage was what inspired him to sail across the Atlantic and join the colony.

The Danish astronomer Tycho Brahe was associated with celestial discoveries during the 16th century. But he was also an alchemist dedicated to brewing secret medicines for elite clients, such as Rudolf II, Holy Roman Emperor.

Renaissance alchemists kept their work secret, and only a few chemical recipes survived into the modern era. Although Brahe’s chemical laboratory, located below his castle residence and Uraniborg Observatory, was destroyed after his death, researchers have conducted a chemical analysis of glass and pottery fragments excavated from the site.

The analysis revealed elements such as nickel, copper, zinc, tin, mercury, gold, lead, and a big surprise: tungsten, which had not been described at the time. It is possible that Brahe isolated it from the mineral without realizing it, but the discovery raises new questions about his secret work.

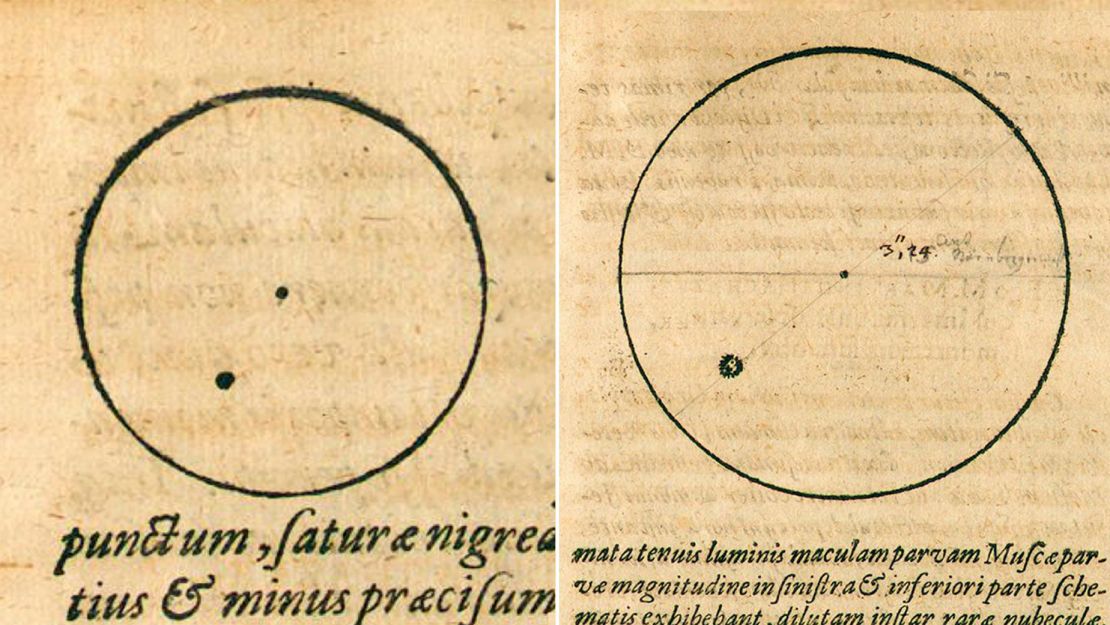

Separately, centuries after German astronomer Johannes Kepler drew diagrams of sunspots in 1607 from his observations of the Sun’s surface, pioneering drawings helped scientists piece together the history of the Sun’s solar cycle.

While each cycle of waxing and waning solar activity typically lasts about 11 years, there have been times when the Sun has behaved differently than expected. Kepler’s long-forgotten drawings, made before the advent of telescopes, were dusted off this year when scientists analyzed them to learn more about the Maunder Minimum, a period of extremely weak and abnormal solar cycles between 1645 and 1715.

Kepler’s drawings were made using a camera obscura, a device that used a small hole in the wall of the device to project an image of the Sun onto a sheet of paper. His drawings captured sunspots, helping astronomers determine that solar cycles were still occurring as expected when Kepler observed them, rather than continuing for abnormally long periods of time as previously thought.

Brahe and Kepler, along with Sir Isaac Newton and Galileo Galilei, were giants who replaced the medieval view of the world with a modern one, said Kar Lund Rasmussen, lead author of the Brahe study and professor emeritus in the Department of Physics and Chemistry. and Pharmacy at the University of Southern Denmark.

This year, the centuries-old works of Brahe and Kepler contributed new pieces that help scientists reconstruct the mysteries of the past.